NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR THE REFORM OF MARIJUANA LAWS

1001 CONNECTICUT AVENUE NW

SUITE 1010-C

WASHINGTON, D.C. 20036

NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR THE REFORM OF MARIJUANA LAWS |

|

|

1001 CONNECTICUT AVENUE NW |

T 202-483-5500 • F 202-483-0057 • E-MAIL NATLNORML@AOL.COM

Internet http://www.norml.org

. . . a weekly service for the media on news items related to Marijuana Prohibition.

February 6, 1997

Record Number Of State Legislatures To Decide On Industrial Hemp In 1997

State Senator Proposes Cultivating Marijuana For Medical Research

NORML Testifies In Support Of -END- MORE THAN 10 MILLION MARIJUANA ARRESTS SINCE 1965 . . . ANOTHER EVERY 54 SECONDS!

Regional and other news

Of the latest week's meetings, Miller wrote on Feb. 1:

Since I have all of you here-this is how it shapes up so far. Out of seven meetings, lowering marijuana's priority for arrest or disbanding the Marijuana Task Force has been mentioned as one of the three priorities for cuts in six of the meetings. All of the meetings have included cuts for "victimless crimes" or cuts in "basic prosecution" which I understand to include low-priority crimes. Mike Lindquist (ex-commissioner) was at my table and voted with me to disband the MTF at the City budget and lower priorities for pot at the county level. Lolenzo Poe (works with Neighborhoods for city) told me that since I have been coming there is "considerable, substantial support" for the ideas we have expressed at these meetings. Erik Sten was facilitator this morning and supported the three items for cuts at our table which included disbanding the MTF. He also said privately that those cuts were exactly what he was recommending to the council at this point. Vera Katz came over to ask how our table came out on smoking (she was in jest). Without a doubt, we have their attention for once.

All I have been asking is simply to lower the priorities for marijuana offenses in the county budget (approx. 16 million annually), and don't build the jails (48 million savings by not jailing pot offenders). In the city budget, disband the MTF. It's $300,000 we can save (plus some change in other departments). I have received support at every table I have been to from a range of a single supporter to one vote shy of unanimous.

I feel like we are making some hay here but the process is 5 more months and I would never claim success too soon. Certainly this is true-

The days of the other side continuing to oppress at all levels and in all ways is over. We are at trials, in front of jurors (thanks Floyd), budget hearings, council meetings et al.

And we've just gotten started......

TD

Southwest Texas State University Prof. Harvey Ginsburg says he has enough signatures for a May referendum. The San Marcos city council decides Monday whether to allow the vote.

Ginsburg stresses that if the ordinance passes, it would not become legal merely to possess the drug within San Marcos city limits.

He says the measure encourages police to show tolerance in enforcing marijuana laws when people suffer from half a dozen designated diseases, such as certain cancers, glaucoma and AIDS. Police would strictly enforce anti-drug laws in all other cases.

Ginsburg says the council has three options on the measure: pass the referendum without a vote, put it on ballot in the May vote, or decline to put the measure on the ballot and reject it.

Mayor Billy Moore says, "If it's the will of the people, then I have no problem putting it to a vote."

Ginsburg says he's pushed for years to allow medicinal use for marijuana.

He says it's clear that marijuana effectively relieves the symptoms of certain diseases, and he cites a New England Journal of Medicine editorial last week that urged lawmakers to allow doctors to prescribe the drug, as proof of the merits of medical tolerance.

Drugs: Todd Cunningham, whose father is a San Diego congressman, is accused of flying marijuana into an airport near Boston.

By Marc Lacey, Times Staff Writer

WASHINGTON -- The Drug Enforcement Administration arrested the son of Rep. Randy "Duke" Cunningham (R-San Diego) earlier this month for allegedly flying an airplane loaded with more than 400 pounds of marijuana into a small airport near Boston.

Todd R. Cunningham, 27, a San Diego bartender, pleaded not guilty to marijuana trafficking and conspiracy to violate drug laws. Authorities said that on Jan. 17, they saw kilogram-size bricks of marijuana unloaded from a twin-engine plane at Lawrence Municipal Airport in North Andover, Mass.

Cunningham was released Wednesday after posting $25,000 cash bail.

His father, a four-term congressman, said he learned of the arrest Friday night, a week after it occurred, when informed by a reporter.

"As a parent, this is the most anguishing thing that can happen to you," Cunningham said in a statement. "We love him. If the charges are true, we are disappointed, and he must face his responsibilities."

Cunningham, a decorated combat pilot and flight instructor, is known in the House for his fiery rhetoric and strong stands on illegal immigration and drug trafficking. He has knocked President Clinton for a "cavalier attitude" toward the problem.

"What we need from our policy leaders and law enforcement is a real war on drugs," Cunningham said in a newspaper commentary last year. "We must get tough on drug dealers, fully fund the war on drugs, and stop drugs at the border."

He noted that Congress passed a law restricting federal judges from ordering the early release of drug traffickers. "Those who would peddle destruction on our children must pay dearly," he said.

Times staff writer Tony Perry in San Diego contributed to this report.

To celebrate an accord struck on Monday to set aside differences over drugs policy and instead to work together to fight drugs smuggling, French Justice Minister Jacques Toubon gave his Dutch counterpart Winnie Sorgdrager a kiss on the cheek.

"I think the conclusion which can be drawn is that we enjoy excellent relations," Toubon told a news conference on the sidelines of a meeting of EU justice ministers.

The two sides had been at loggerheads over drugs policy, with France accusing the Netherlands, through its liberal drugs policy, of making it possible for young people to buy drugs to circulate elsewhere.

Although drugs are illegal in the Netherlands, small amounts of soft drugs can be bought in so-called coffee shops and the police turn a blind eye to the possession of small amounts of hard drugs.

Under the accord the two sides will increase cooperation at customs.

Sorgdrager said the two sides, along with their EU partners would also investigate the availability of drugs in prison and cooperate with eastern European governments to try to stem the flow of designer drugs like ecstasy and crack.

PHOENIX - Arizonans either knew what they were doing when they voted last November to allow doctors to prescribe marijuana or they were duped and wish they had it to do all over again.

Either way, the Legislature plans to have the final say.

The debate over Proposition 200 reignited yesterday, three months after voters overwhelmingly approved the so-called medical marijuana initiative. The new law also requires treatment instead of jail time for first-time drug offenders and orders the release of some non-violent offenders already in prison.

Opponents and supporters released conflicting polls yesterday about whether Arizonans still supported the measure: The opponents' poll said voters would like to repeal Proposition 200; the supporters' survey found that voters were satisfied with what they did.

Each side challenged the other's results.

At the Capitol, a group of Republican and Democratic legislators begged off the question of public opinion and instead proposed a series of bills that would water down Proposition 200.

The proposals would narrow the list of drugs that could be prescribed to one - marijuana - and then only if the federal government agreed.

A second bill would place tighter controls on releasing drug offenders from prison.

A third measure would send drug offenders to prison if they don't agree to treatment.

"Our approach is not to thwart the will of the people on Prop. 200, but to implement it in a rational, reasonable way," said Senate Judiciary Chairman John Kaites, R-Glendale.

Maricopa County Attorney Rick Romley fired the first shot yesterday, releasing the results of an opinion poll showing what appeared to be a 180-degree turnaround among the state's registered voters.

It found that 85 percent of those surveyed believe Proposition 200 should be changed and that 60 percent believe it should be repealed. Even with that kind of opposition, though, 64 percent felt doctors should be able to prescribe marijuana to patients under certain circumstances.

Not surprisingly, the poll also found a huge majority opposed total legalization of drugs and the early release of violent offenders or offenders with long histories of drug arrests.

Those issues were not addressed in Proposition 200.

The survey was conducted by Bruce Merrill, director of the Arizona State University Media Research Center, and paid for by the Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America.

Several hours after Romley's news conference, one of the groups responsible for Proposition 200 released its own poll, which showed Arizonans still behind the ballot measure and are in no mood to have the Legislature tinker with it.

The survey, conducted by Fairbank, Maslin, Maullin & Associates for the group Arizonans for Drug Policy Reform, found 56 percent of those asked would still vote in favor of Proposition 200.

More than half - 53 percent - want Romley and others to stop efforts to repeal the measure, and 59 percent felt that voters had made their decision and should be allowed to stand by it.

Paul Maslin, one of the pollsters, said the results should not have been unexpected because, "These are the same people who made their decision in November."

He said Merrill's poll was biased and structured in a way to guarantee the outcome, using scare tactics and loaded questions.

The question about whether voters still supported Proposition 200, he said, was preceded by 17 other questions, many focusing on drug use by children, the release of violent criminals and legalizing drugs.

Merrill dismissed Maslin's charges and said the conflicting results don't necessarily mean either poll is flawed.

"It's one of those gray areas of polling where you've got two advocacy groups," he said. "The groups have a difference in what the bill represents. Our group tried to test what they thought were the unintended consequences."

He said the other polling group could be accused of bias as well because it prefaced its question with the reminder that Proposition 200 passed with 65 percent of the vote.

"By putting that in, you're saying, `Are you going to let the politicians reverse the will of the people?' " he said.

The furor over Proposition 200 is unlikely to fade away with the Legislature planning to consider bills that would blunt many of its effects.

Sam Vagenas, one of the measure's chief proponents, called the bills an attempt to gut Proposition 200.

"Proposition 200 is law," he said. "There's no such thing as implementing it. It's their burden to repeal it, not our burden to get them to enact it."

But Kaites and others said the Legislature needed to fine-tune the measure to prevent any unintended consequences. The package he and others are proposing will include measures to:

The third bill would hinge on the federal government's approval. Federal officials so far have threatened to prosecute doctors who prescribe illegal drugs, but Kaites said the Legislature can ask Congress and President Clinton to review the medical use of marijuana.

Here is the abstract:

"Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 1996"

Did You Know...

..between year-end 1985 and midyear 1996 the incarcerated population grew from 744,208 to 1,630,940, an average growth rate of 7.8 percent a year.

Were You Aware...

..in the previous 12 months the number of inmates in the Nation's prisons and jails rose an estimated 69,104 inmates or 1,329 inmates per week. Since 1990 the total population in custody has risen to more than 482,200 inmates, the equivalent of 1,686 inmates per week.

Statistics Show...

..at midyear 1996 Federal and State prison authorities and local jail authorities held in their custody 615 persons per 100,000 U.S. residents.

Findings Indicate...

..four States had 12-month growth rates of more than 14.0 percent: Nebraska, Montana, North Carolina, and Oregon. The District of Columbia (down 6.9 percent), New Hampshire (-0.7 percent), and Connecticut (-0.2 percent) recorded declines.

The Facts Are...

..an estimated 8,100 people less than 18 years old were held in adult jails at the end of last June. Over two-thirds of these young inmates had been convicted or were being held for trial as adults in criminal court.

To obtain a copy of BJS' new release, "Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 1996" (NCJ 162843), please see "Ordering Directions" at the end of JUSTINFO or point your Web browser to http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs.

JUSTINFO, an electronic newsletter service sponsored by the U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, is published the first and fifteenth of each month. It provides the latest criminal justice news, information, services, and publications.

Former Gov. Edward "Ned" Breathitt told a group of farmers yesterday that they should be allowed to grow industrial hemp.

"I strongly support it - anything we can do" to diversify Kentucky farms, Breathitt told about 100 people gathered in Lexington for the Community Farm Alliance's annual meeting. Breathitt acknowledged there are many obstacles to restoring hemp as a legal crop in Kentucky, not the least of which would be marketing. "It's not going to be easy; you're just going to have to build a momentum for it."

Both the Community Farm Alliance, which has about 900 members statewide, and the larger Kentucky Farm Bureau have endorsed hem as a legitimate crop. Last week, hemp advocates won a round when a district judge in Lee County ruled that state law unconstitutionally treats hemp, which is grown for fiber and is not intoxicating, the same as the mood-altering drug marijuana.

The ruling came in a test case by actor Woody Harrelson. Randy Barker, a Fleming County farmer and president of the Community Farm Alliance, called the ruling "a start."

"A judge has realized and admitted in public there's a difference. Marijuana and hemp are not the same." Barker said hemp won't replace tobacco in Kentucky's farm economy but could be part of the mix. "It's not God's answer for farmers. But it is an alternative."

When Dr. David S. Alberts was treating cancer patients in the early 1970s, he sometimes suggested a cheap but illegal remedy for the nausea associated with chemotherapy.

"I would basically give them a prescription. I recommended that this patient take marijuana for medicinal purposes," said Alberts, who was working in San Francisco at the time.

Today he is associate dean for research at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, director of cancer prevention and control at the Arizona Cancer Center, and a vocal supporter of the medicinal use of marijuana.

"It was a preferred drug for nausea back then," Alberts said. "And there's no question that it has major medicinal qualities for cancer patients.

"And when you have a law on the books that condones this, I don't know why you wouldn't use it," he said. "I don't see why there is a controversy in Arizona anymore."

Last year voters in Arizona and California passed propositions permitting doctors to prescribe marijuana for medical uses.

In response, Attorney General Janet Reno said doctors who do so could lose their prescription-writing privileges, be excluded from Medicare and Medicaid, and even be prosecuted.

Some doctors say marijuana relieves internal eye pressure in glaucoma patients, controls nausea in cancer patients on chemotherapy, and combats the severe weight loss seen in AIDS patients.

But Clinton administration officials say the efficacy of such treatments is unproven.

The prestigious New England Journal of Medicine last week came out in favor of medicinal uses of marijuana.

Journal editors called the threat of government sanctions misguided, heavy-handed and inhumane.

"I agree with the editor of the New England Journal wholeheartedly. I agree with everything he said," said UA pharmacologist Paul Consroe, who has studied the effects of marijuana for 24 years.

"There's no question that we can show that marijuana does certain things of a therapeutic nature," Consroe said.

"I'm not saying that it is better than what we already have on the market. But it does lower the pressure in the eye (of glaucoma patients), and that's something that can be measured."

The federal government lists marijuana as a schedule 1 drug along with heroin and LSD.

Schedule 1 drugs are defined as having high abuse potential and no recognized medical use, Consroe said.

If federal officials admit marijuana has valid medicinal uses, they'd be forced to reclassify it, he said.

"You see where the government is coming from? They're scared," he said.

Tucson glaucoma expert Dr. Jeffrey S. Kay said marijuana lowers eye pressure but is not as effective as eyedrops designed for glaucoma patients.

"My feeling is that if they're unable to take conventional eyedrops it may be an alternative, but it certainly would not be my first choice," said Kay, of Tucson Glaucoma Specialists.

"If my patients want to use it, I'll leave it up to their discretion, but there are other medications that are equally effective or more effective without the side effects you would get from smoking marijuana," Kay said.

The same goes for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in chemotherapy patients, said Dr. Sydney Salmon, director of the Arizona Cancer Center.

In the early 1970s, when Alberts was suggesting marijuana to some of his cancer patients, such anti-nausea drugs as Zofran and Kytril weren't available.

Today those drugs are "extraordinarily effective" in combating the problem, and there's even a synthetic version of THC, marijuana's active ingredient, available in pill form.

"We've had new drugs that are more potent and effective than marijuana or its derivatives, and with far fewer unpleasant side effects," Salmon said.

But Alberts said Zofran and Kytril are "incredibly expensive, so expensive that few people can afford them."

And while the pills can take several hours to deliver their peak effect, the anti-nausea effects of smoking marijuana are almost immediate, he said.

"There are some cases where marijuana will work when nothing else does," Alberts said.

"My attitude is that we should do everything we possibly can to support the cancer patient," he said. "If smoking marijuana is useful to (patients), it should be available to them."

AIDS patients use Marinol, a synthetic version of THC, as an appetite stimulant and to control the nausea sometimes associated with the drug AZT. Tucson AIDS patient Jason Vogler said Marinol helps him but doesn't work for everybody.

Marijuana should be available to AIDS patients who aren't helped by Marinol and other medications, he said.

"This is not about getting high," Vogler said. "I'm just hoping this will help a notch group that might not find relief elsewhere.

"We place a great deal of trust in the judgment of physicians, and we have to operate under the assumption that physicians are going to use this as a valid pharmacological item."

When Gilpin County juror Laura Kriho decided to follow her heart instead of the letter of the law when deciding a drug possession case last year, she found herself at the center of a maelstrom of controversy over jury nullification. With her one vote, Kriho hung the jury and brought contempt of court charges upon herself. Now, nine months later and almost four months after her trial, Kriho is still unsure of her fate.

Why?

Well, according to the clerk for First Judicial Court Judge Henry Nieto, who heard the evidence during Kriho's Oct. 1-2 bench trial for contempt of court, a verdict in the case has not been reached because "the judge is real busy. He'll get to it when he gets to it. He has to take care of a lot of things, like other trials."

Too busy. Strange, considering Nieto denied a continuance motion by Kriho's attorney Paul Grant in September, saying the issues in the case would be easy to decide.

Or it might be because Judge Kenneth Barnhill who originally heard Colorado v. Michelle Brannon (the case which Kriho heard) retired Friday, Jan. 17, and with his retirement avoids any possible official sanctions that could result from his move to put a juror on trail for her beliefs.

Regardless of his reasons, Nieto's failure to render a verdict in the case probably won't cost him, even though a specific state statute says it should.

Kriho was brought up on contempt charges by prosecuting attorney Jim Stanley because she allegedly failed to point out that she did not believe in drug laws during jury selection for the trial of a 19-year-old charged with possession of methamphetamine. But, her attorney Paul Grant says, to charge and try Kriho is wrongheaded because his client was never specifically asked questions about her feelings in regard to drug possession laws.

More importantly, he says, jurors haven't been held accountable for their decisions since before the Revolutionary War.

"This case is bizarre. Jurors haven't been prosecuted for their deliberations in the jury room for hundreds of years. These guys want to reverse that. These guys want to go back to the 17th century. They put her on trial for her political associations for her beliefs ... for her philosophy. None of that is the court's business," Grant says.

Now almost four months since the conclusion of the contempt trial, Grant and Kriho are both wondering whether or not she is facing punishment for standing up for what she believes in. The U.S. Constitution states every citizen has the right to a fair and speedy trial (including a verdict), yet Nieto has yet to come to a decision on his client's fate, Grant says.

"It's not supposed to take this long. Appeals can take months or years to come to a verdict, but not trials. The statute says a judge must render a verdict in 90 days. But if he doesn't render the verdict within that time frame, it doesn't mean the verdict won't count when it is issued."

And in an interesting twist, Nieto may be putting his salary on the line by missing the 90-day deadline. According to a little-known state statute, if any judge of a Colorado district court fails to render a judgment in a case he has taken under advisement within 90 days, as Nieto has, he or she must forfeit their quarterly salary. In Nieto's case, that equals a cool $20,000 or more.

Whether or not anyone will actually enforce the statute, which has been on the books since before 1912, is up to ... well, that's an interesting question, too.

In the opinion of Richard Collins, associate dean of the law school at the University of Colorado, the statute is akin to an unloaded gun: it can keep judges in line through menace, but cannot do any real damage.

"The mystery of this statute is, who is meant to enforce it? By its terms, the interested people - that is Kriho and her opponents, the people all excited about this - have no right to enforce (the statute) because their interests are unaffected by it. So the question is then, who does have a right to enforce it?" Collins says. "If someone decides to suddenly say that because this Kriho case is really a political football and there are all kinds of people yelling and screaming about it and the Internet is just smoking with it, therefore we'll penalize this judge even though we don't penalize any other judges - that just isn't going to fly."

If the past is any indication, Nieto will be able sit on Kriho's case as long as he wants to without fear of financial sanction, according to a staffer in the state government.

"Generally what has happened when people have attempted to enforce the statute in the past, they've contacted the Treasurer's Office and they have received back... the statement that the (statute) has never been enforced because of concerns over the constitutionality of it," says Kim Coles of the state Judicial Department.

What will the verdict be when it is finally handed down by Judge Nieto? Grant says he doesn't want to speculate because, as he puts it, he doesn't have a crystal ball, but, "If she is convicted, we'll appeal, if she's acquitted, we'll celebrate."

Neither Kriho or Stanley will comment on the specifics of the case. Grant says his client does not want to say anything to the media while the case is still undecided. Stanley, like Nieto, seems to be too busy. "All the information - files, transcripts, legal documents - is available at the Gilpin County Courthouse," he says brusquely before hanging up.

Perhaps, Grant suggests, the Kriho trial is a sign of things to come in Gilpin County. Judge Barnhill recently brought up a lawyer on contempt of court charges, Grant says. Judge Nieto will hear the case, he adds.

"They are going to hold that trial without a jury too. Now we're putting attorneys on trial in Gilpin County. It's very interesting."

Photo caption:

According to a state statute, Judge Henry Nieto should pay for his tardiness in returning a verdict in the Laura Kriho case, but whether he will remains to be seen.

Re-distributed by the:

"This Is Smart Medicine"

A doctor argues that marijuana can ease patients' suffering in ways nothing else can.

By Marcus Conant

Anyone who has ever smoked marijuana will tell you he gets hungry afterward. That kind of anecdotal evidence led doctors and patients to experiment with marijuana as a treatment for extreme nausea, or wasting syndrome. I have seen hundreds of AIDS and cancer patients who are losing weight derive almost immediate relief from smoking marijuana, even after other weight-gain treatments-such as hormone treatments or feeding tubes-have failed. But it's not just individuals who have recognized the medicinal benefits of marijuana. No less an authority than the FDA has approved the use of Marinol, a drug that contains the active ingredient in marijuana.

The problem with Marinol is that it doesn't always work as well as smoking marijuana. Either you take too little, or 45 minutes later you fall asleep. Even though insurance will pay for Marinol-which costs about $200 a month-some patients spend their own money, and risk breaking the law, for the more effective marijuana. That's fairly good evidence that smoking the drug is superior to taking it orally. How would we keep patients from giving their prescribed marijuana to friends? The same way we keep people from abusing other prescription drugs: by making patients understand the dangers of giving medication to other people. A physician who prescribes marijuana without the proper diagnoses should be held up to peer review and punished. There are drugs available at the local pharmacy-Valium, Xanax, Percodan-that are far more mood-altering than marijuana. They aren't widely abused. It's not important that a few zealots advocate the wholesale legalization of marijuana. The federal government can't craft policy based on what a few irrational people say. This is a democracy, and what the people of California voted for was to make marijuana available for medical use for seriously ill people.

For skeptics, a study devised at San Francisco General Hospital would test the benefits of smoking marijuana once and for all. It, too, was endorsed by the FDA-but the federal government won't provide the marijuana for the study. Washington recently offered to fund a $1 million review of literature on medical marijuana, but it refuses to allow a clinical trial, which is what's really needed.

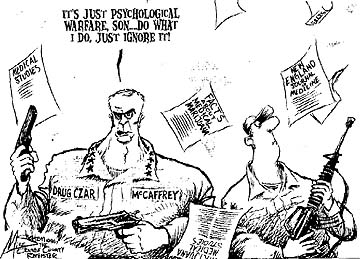

When citizens even speak up in favor of legalizing marijuana for medicinal use, as happened this fall in California and Arizona, the government tries to stop them. Gen. Barry McCaffrey and the Justice Department have threatened to revoke the prescription-drug licenses of doctors who prescribe marijuana. This is a truly dangerous step. The government has no place in the examination room. Our society has long felt that certain relationships require privileged communication, such as those between a priest and a parishioner or a lawyer and a client. If a patient wants to discuss marijuana, I don't want to have the responsibility of reporting him, and I have to feel comfortable that the patient will not report me. This is a First Amendment issue of freedom of speech between doctor and patient.

Perhaps the most persuasive argument for medicinal marijuana I've encountered came two years ago, when the California Assembly was debating a medical-marijuana bill. One GOP assemblyman said he had had a great deal of trouble with the issue. But when a relative was dying a few years before, the family had used marijuana to help her nausea. That story helped the bill pass. Wouldn't it be awful if people changed their minds only after someone close to them had died?

Conant, a doctor at the University of California, San Francisco, has treated more than 5,000 HIV-positive patients in his private practice.

The claims are unproven, but many patients say the drug helps them.

By Geoffrey Cowley

Susan Nelson Spent most of 1978 watching her husband, Don, retch almost constantly. His body fought so hard to expel the chemicals used to treat his testicular cancer that, after 18 months, his battered esophagus ripped, causing tissue damage that has plagued him ever since. A decade later, it was Susan's turn. She developed lymphoma in 1989, and she, too, underwent chemotherapy. But in four months of treatment, she vomited only once. Instead of heading for the bathroom when she felt a surge of nausea, she took matters into her own hands: she fired up a joint.

Susan Nelson is no dopehead. She grew up in a military family, and never even experimented with pot as a '60s teenager. But she wasn't about to relive her husband's experience. The anti-nausea drug her doctor prescribed did wonders for her digestion, but it also lowered her inhibitions, causing inexplicable urges to throw plates and roll burning logs on the living-room floor. Smoking marijuana may have broken the law (she bought it from fellow patients), but it didn't break her dishes. "When I smoked it," she recalls, "you could still trust me."

Americans may frown on recreational pot smoking, but as recent votes in California and Arizona make clear, a lot of people favor leaving folks like the Nelsons alone. The states' initiatives won't have much practical effect (they free doctors to recommend marijuana without creating legal supplies of the drug). Still, the measures have revived an important and long-neglected question: does pot ever make good medicine? Federal drug-enforcement officials say the drug is both useless and dangerous. They're challenging the new initiatives in court and vow to punish doctors who prescribe pot to their patients. But proponents claim marijuana can help control glaucoma, forestall AIDS-related wasting, ease the nausea brought on by cancer chemotherapy and counter the symptoms of epilepsy and multiple sclerosis. The claims are largely unproven, but they warrant some serious attention.

Marijuana's basic mode of action is well known. Several years ago, researchers discovered that the body makes a chemical closely resembling THC, the main active ingredient in cannabis, and that the brain has receptors designed specifically to receive it. The receptors are concentrated in the brain regions responsible for motor activity, concentration and short-term memory. As anyone who ever inhaled will attest, marijuana can disrupt all those functions.

The question is whether it can do anything else. For nearly three decades the government has listed marijuana as a "schedule I" drug, a designation reserved for substances with no apparent medical value and a high potential for abuse. Barry McCaffrey, director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, stoutly defends that ruling, saying there is "no convincing scientific evidence" that marijuana offers benefits that a person can't get from approved prescription drugs.

Where glaucoma is concerned, McCaffrey has a point. It's well known that smoking marijuana can reduce pressure within the eye, a hallmark of the disease. But the drug may also reduce the blood supply to the optic nerve-the last thing a glaucoma sufferer needs-and it doesn't seem to prevent blindness. Even if marijuana could save eyes, smoking it enough would take extraordinary effort. "In order to substantially reduce eye pressure," says Dr. Harry Quigley of Johns Hopkins University's Wilmer Eye Institute, "you'd have to be stoned all the time." When researchers tried dissolving THC in eye drops, they succeeded only in irritating people's eyes, but other compounds proved more useful. As a result, glaucoma patients can now choose from a number of potent topical treatments. The latest, a once-a-day eye drop called Xalatan, is virtually free of major side effects.

Marijuana may not cure glaucoma, but it has other claims to respectability. People have used it for centuries to stimulate appetite, and an unknown number now use it to combat the wasting associated with AIDS. No one knows how much good it's doing-the drug-control agencies have recently thwarted studies intended to answer that question-but some experts suspect the benefits are modest. The wasting syndrome doesn't stem solely from a lack of appetite, says Dr. Donald Kotler, an immunologist at New York's St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital. The patient may have an intestinal infection that blocks the absorption of nutrients, or a neck tumor that interferes with swallowing.

Skeptics also note that the FDA has already approved several effective remedies for wasting. To stimulate appetite, patients can take Marinol, a synthetic version of THC that comes in pill form, or Megace, a derivative of the hormone progesterone. In premarketing studies, AIDS patients who took Megace for 12 weeks gained an average of 11 pounds, while those getting a placebo lost 21. Since AIDS takes a particular toll on muscle tissue, the FDA has also approved several muscle-building steroids (testosterone and its kin) as AIDS treatments. Patients with good insurance can also get synthetic human growth hormone, a bone and muscle builder that costs $1,000 a month.

Yet as many patients have discovered, plain old pot may stil1 have a valuable role. Keith Vines, a 46-year-old San Francisco prosecutor, considers himself a stalwart in the war on drugs. As an assistant district attorney, he has spent years putting street dealers in jail. As an AIDS patient, he has seen his body threaten to disintegrate. "Three years ago my ribs were protruding," he says. "I was terrified to get on the scale." He wanted to enroll in a study of human-growth hormone, but participants had to eat three meals a day, and he could hardly force down one. He tried several drugs-including Marinol, which often left him too blasted to function-but nothing worked until he joined a local buyers' club and started smoking pot. Once he took that leap, he qualified for the humangrowth-hormone study, put on 45 pounds and managed to salvage his job. "Without marijuana," he says earnestly, "I would be dead."

Like AIDS-related wasting, the nausea from cancer chemotherapy is readily treated by prescription drugs. But those drugs are expensive, they don't always work and they're not always harmless. Their warning labels are littered with phrases like "hives," "impotence," "difficulty breathing," "tremors and rigidity" and "leukopenia" (a drop in white blood cells). Marijuana isn't riskfree-its smoke contains a number of carcinogens-but it's less toxic than many prescription drugs. There is no recorded instance of a death from overdose. And because people consume it one puff at a time, feeling the effects as they go, they can easily tailor their intake to their needs.

That's a big advantage for people with chronic pain or with spastic disorders such as multiple sclerosis. Whereas prescription drugs may zonk them out for the whole day, marijuana lets them respond directly to their symptoms. No one has conducted trials to gauge marijuana's genuine therapeutic effect on pain and spasms. But that doesn't much concern 39 year-old Andrew Hasenfeld, who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1980. He tried the prescription drug bactofen, but it never relieved the spasms, the stiffness, the sensation of "being all locked up." He resorted to marijuana six months ago, at the urging of fellow sufferers in Amherst, Mass., and the result was dramatic. "There's no comparison with any drug I could buy in a pharmacy," he says. Few people would argue that Andrew Hasenfeld, Keith Vines or Susan Nelson belongs behind bars. ("I'm already in a wheelchair," says Hasenfeld. "Isn't that enough?") And though recreational pot smokers can get involved with harder drugs, it's hard to see how easing one's nausea, wasting or muscle spasms could cause what the drug office describes as "a downward spiral of self-destruction." Still, federal regulatory policy can't rest entirely on individual testimonials. As McCaffrey argues in a forthcoming "myths and truth" position paper, "drug policy must be based on science, not ideology." Approving marijuana as a prescription drug would require organizing clinical trials, identifying appropriate uses and finding ways to regulate its cultivation and sale. Those aren't insurmountable obstacles; morphine has been used medically for years. But federal policy has long discouraged clinical research with marijuana. The drug-control office is now pledging that "any serious marijuana research request will be considered." Perhaps that will begin to clear the smoke.

With Mary Hager in Washington, Adam Rogers in New York, Claudia Kalb in Boston and Patricia King in San Francisco.

Reformers will not love the story. But it's a must-read nonetheless. Rosin uses a visit to Dennis Peron's re-opened Cannabis Cultivators Club to skewer the cause of medical marijuana, and sniffs at the new commercialization of marijuana.

(It should be noted that the creator of "Beavis and Butthead" was quoted some years ago (by Rolling Stone or perhaps Spin?) saying that his characters were too dumb to know anyone who would sell them pot. - ed.)

by Hanna Rosin

Opening day at San Francisco's Cannabis Cultivators Club, and the line at the door eats up the whole block. It is a well-mannered line, considering who is standing in it: a bunch of homeless men streaked with grime, a very large and fierce-looking woman in a wheelchair, a gaggle of mulatto transvestites. Near the front of the line, a woman with pronounced buck teeth is straining, with slow and deliberate jabs, to place a feather earring in the ear of the man standing in front of her, a difficult task given that the man has no ear, merely a gnarled nub of cartilage. She giggles; Van Gogh smiles. A tall, gaunt man guards the door. He checks to see that each person has a letter of diagnosis from a doctor, legally qualifying him or her to buy marijuana. The gatekeeper is calm, composed, and so are the men and women that file silently past him. There is a sense about the scene of something captured in negative. It is as if the rotting of late '60s San Francisco described by Joan Didion in Slouching Towards Bethlehem has been preserved in reverse; the characters are the same, but the center was holding.

Inside the club, order seems to reign, as well. The computers are up, the phones are ringing. Reporters chase down sick people in wheelchairs. The reporters are here because today is a news event: the relaunching of the mothership, as the club is known to its grateful patients, marks the coming out of California's medical marijuana movement after years in hiding. Founded in 1992, the club existed in an uneasy truce with the city of San Francisco, selling pot to some 12,000 customers designated as medical patients. It grew to become by far the largest medical marijuana club in the state, serving as many patients in a day as the other seven or so clubs together might serve in a week. Then, in August, 1996, state narcotics agents raided the club and shut it down on a host of marijuana possession and distribution charges. Three months later, California voters, by a margin of 56 to 44 percent, passed Proposition 215: The Medical Marijuana Initiative, making it legal to smoke marijuana in California with the approval or recommendation of a doctor. A local judge promptly gave the club permission to reopen and designated the club's owner, a former (and often-convicted) marijuana dealer named Dennis Peron, as a caregiver (which is to say, pot provider) for up to 12,000 patients.

Today is the first day of the new era, and Peron is eager to make a good, caregiving sort of impression. Dressed in an argyle sweater and blue oxford with a pinstriped tie, he glides to the middle of the room, climbs up on a coffee table ringed with doting patients and speaks: "If we can't get in touch with your doctor we can't sell you marijuana. We are law makers, not law breakers." He then adds, with a mixture of melodrama and mock asides, "We will never abandon you. We will save the people in pain. Once you get your card, you will see the marijuana smoke. Just like the old days. Oh, that smell...."

A cynical listener might discern here an attitude that seems less like that of the nurturing caregiver, and more like that of, how to put it, an old pothead eager for the good times to roll again. The cynical listener would be on to something. Late in the afternoon, when all the reporters have cleared out to meet their daily deadline, Peron hushes the crowd again. "I know a lot of you have waited a long time and you are sick and you have to go through this bullshit. And it is bullshit. Today we have to go through this bullshit for a thousand years of love. I've missed you so much. One week of bullshit, a thousand years of love." One of Peron's deputies rushes outside to carry the message to those who did not make it in that day. "Don't worry," he eases them. "It will be just like before. Just come back tomorrow. Today is the first day so things are a little, you know. Just come back tomorrow."

The passage of Proposition 215 surprised even its most zealous supporters. In the months before the November election, they fought what they thought was an uphill battle against an enemy that tried to portray them as a front for the seedy drug dealers on Market Street. Tough-talking law enforcement officers like Orange County Sheriff Brad Gates warned that the initiative "would legalize marijuana, period!" But the pro-215 activists knew better than to engage in that argument. They stuck to their line: the referendum was simply about limited, medical use of the drug, and then only in extreme cases. They made the debate one of compassion versus suffering, plastering billboards across the state with images of the hollow-faced sick and dying, the bloated and bald Helen Reading, 43, breast cancer; the furrowed and frowning Thomas Carter, 47, epilepsy. "You have just been told you have terminal cancer," reads one poster. "Now for the bad news: Your medicine is illegal."

Of equal importance in their electoral victory, the pro-215 activists tailored their image midstream; they hired a pinstriped professional, Bill Zimmerman, to run the campaign, and to run it at a conspicuous distance from people like Dennis Peron: "He was pictured on election night smoking a joint and saying, `Let's all get stoned and watch election night returns,'" Zimmerman recalls. "That kind of behavior supports the opponents' view that we are a stalking horse for legalization.... He could ruin it for the truly sick." Zimmerman's images stuck. The New York Times ran a sympathetic portrait of "an arthritic, HIV-positive cabaret performer," under the headline "marijuana club helps those in pain." Sympathetic, and gullible. With its breathy, tenderhearted reporting, the intrepid Times reporters implicitly tried to correct Sheriff Gates. See, the article said, these people smoking these joints are cripples, real ones, and cancer patients, real ones. They are merely looking for a little easing of their pain, not fronting for the de facto legalization of pot.

The truth about the medical marijuana movement is much simpler, and blindingly obvious after a day in Peron's club. The movement is about the compassionate extension of relief to sick people--THC, the active ingredient in marijuana, offers some sick people a cheap, effective surcease from pain--but it is also very much, and primarily, about legalization. The movement may feature billboards of the infirm, but in the offices of its activists you are more likely to find a different poster, a stoner classic: the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution were written on hemp paper.

Both the hemp poster and the sad faces of Helen Reading and Thomas Carter are, in different ways, part of an overall campaign to make pot wholesome--to turn it into something as legitimate as, say, over-the-counter cough syrup. The medical marijuana movement and the legalization movement share a common language and common idea. Most of the medical marijuana clubs that have sprung up in California in the past seven years are much stricter than Peron's, which represents the outside edge of respectability and adherence to the law. These more proper establishments run would-be clientele through the checklist of rigid protocols a patient must submit to--a signed doctor's recommendation, a detailed health questionnaire, follow-up visits to the doctor. But, if you talk to the people who run the clubs for any time at all, you will notice that mostly what they talk about is not medicine but legalization--the same standard jargon of hemp and drug wars and government oppression and narcs. One of the strictest clubs in the state is in Oakland, a small place run by a righteous young man named Jeff Jones, who is rigorous in following the letter of the law. The law says, basically, that marijuana may only be sold to people who have a legitimate medical need for it--people, in other words, who could be made to feel better by a toke or two. "But wouldn't marijuana make anyone feel better?" I asked Jones. "Now you're getting the point," he answered, approvingly.

Legitimation through medicalization is not a novel tactic in drug history. In their times and places, opium, laudanum, cocaine, nicotine, alcohol and LSD have been packaged as cures. At the turn of the century, middle-class medicine cabinets were stocked with doses of morphine, codeine and laudanum. The tincture of opium in spirits was known as "God's own medicine." Fussy baby? Try Children's Comfort, or Mrs. Godfrey's soothing syrup, a healthy shot of opium in wine. Public health officials estimated at the time that one in every 200 Americans was a drug addict, most of them happy (giddy, even) housewives. And now, we have pot, the medicine.

The medicalization of marijuana is an attempt to recapture something lost, the brief moment of status pot enjoyed in the 1970s. It is hard to recall now how very near it seemed marijuana was to national legalization then. That year, a government lawyer named Keith Stroup launched the first serious effort to mainstream pot, a group called, aptly, NORML -- the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws. With his charming lisp and velvet bow tie, Stroup succeeded in making marijuana normal, even banal, a trajectory wonderfully documented in Dan Baum's Smoke and Mirrors. Within two years, Stroup had convinced eleven states to make marijuana possession the legal equivalent of a parking violation. School drug abuse books "dismissed marijuana as less harmful than tobacco," writes Baum; "one advised kids to use a water pipe to cool the smoke and avoid burning holes in their clothing."

Then Jimmy Carter picked a drug czar, Peter Bourne, who was the Beltway version of Timothy Leary. Bourne convinced Carter to take the first crucial step toward legalization--replacing criminal penalties with civil ones. The president announced his decision in a speech; every sentence on drugs was written by Keith Stroup. "I support legislation ... to eliminate all federal criminal penalties for the possession of up to one ounce of marijuana," Carter announced.

The end came suddenly, crashingly, with Ronald Reagan. The new president picked up Nixon's War on Drugs and added the force of the U.S. Army, the FBI and the CIA. His wife warned parents to "Get Involved," their kids to "Just Say No." The new official drug abuse pamphlet called Parents, Peers & Pot asked, "Is your child keeping late hours? Has his schoolwork suddenly gone bad? [D]oes she look sloppy or dirty?" and blamed this teenage epidemic of sloth and bad hygiene on marijuana. "The mood toward drugs is changing in this country, and the momentum is with us," Reagan thundered in a radio address. "Drugs are bad, and we're going after them." The culture retreated, with a large dose of self-flagellation. For years, the prophets of marijuana lay holed up in dim, seedy head shops, muttering about the narcs. But now, once again, California is sending them a signal.

The excitement of a new dawn is felt on this opening day of the club, and it is hardly dampened by the dim, fusty interior. The place is divided into three spacious, though windowless, rooms and looks like the messy common room of a college dorm, with bits of origami and amateur "art" hanging from the ceiling, mismatched couches placed askew, ranging in color from bruised to rust to dung. The first person I run into is Andrew, a middle-aged black man with clipped dreads. "You're a journalist," he observes, when he sees me taking notes. "I keep a journal." Having established this common bond, he feels comfortable showing me some of his work. "Before I started writing, life wasn't worth two puffs of coke," he explains as a prologue. I expect to see some more revelations in the journal, maybe some bad poetry. But all I can make out on the first page is "shorts suck" with a crude drawing of Andrew in boxer shorts.

I try to change the subject, and ask him why he's here. He suffers from a disease not mentioned in the posters, but which turns out to be a relatively common ailment among the club's patients. "I have insomnia," he explains. "Also, I get migraine headaches." Before I can ask Andrew's last name, my arm is grabbed from behind by a woman I soon find out is Pebbles Trippet, a Berkeley activist who wants me to listen to an on-camera interview she's doing with the TV equivalent of High Times.

Pebbles is a woman who once was conventionally lovely, with clear blue eyes, a straight nose and long blond hair. She has preserved these features of young beauty--the eyes, the long hair--but added a layer of must and cobwebs and wrinkles. She is draped in what looks like an old rug with pockets, a tattered rainbow lei, cracked leather sandals and mismatched socks. The effect is jarring, like a skeleton with pretty hair. "I am a medical marijuana user," she declares to the camera. "I have self-medicated for decades. They have tried to jail me in three cities--Contra Costa County, Sonoma County, Marin County."

I ask her what's wrong, trying to sound sympathetic.

"I get migraine headaches."

How does smoking marijuana help?

"I use it as prevention. I have not had my weekly headache since childhood. It has to be really good bud, and it relaxes me. It takes me to a higher spiritual place. It's part of my religious belief; it's a sacrament. Herbs and humans need each other. I'm a nature worshiper, and I can sanction anyone who uses Mother Nature's herb."

Pebbles introduces me to her friend Buzzy Linhart, a roly-poly, balding man with stiff whiskers the color of straw. Buzzy is wearing an eye patch. "If not for marijuana, Buzzy might well be blind," says Pebbles.

I ask Buzzy if I can see his doctor's note.

"I have to update my doctor's letter. I gotta go back to Berkeley and see if he's, uhhh, in the country."

Pebbles presses him, "Tell them about your disease."

At this point Buzzy launches into a dialogue I have great difficulty following: "I found my old pal marijuana saved my life ... the love herb ... gather the earth back together ... Reagan ... prostitution laws." Suddenly, he says, "This is important. Write this down," giving me hope I will get something useful. "Do you know who was the co-author of Bette Midler's `Got to Have Friends'?"

Uh, no.

"Buzzy was the co-author. Tonight, she's opening in Las Vegas. People like her should not forget the people who launched their career."

I make a mental note. Buzzy and Pebbles have taught me an important lesson. People who get high are very difficult to interview, for several reasons: (1) They can't complete a thought. They speak in strings of non-sequiturs; they dig for socially heavy meaning but can only come up with verbal scraps-- snatches of movement jargon from the summer of love, stoner observations overheard in the parking lots at Dead shows, stray dialogue from "Gilligan's Island." (2) They are paranoid. During our interview, Pebbles often strays out of the camera's range to stand very close to me and look at my notes. This is distracting because I do not want her to see, say, my description of her outfit. I resolve to write in very small letters. It is also distracting because it affords me an uncomfortably close view of her teeth, the kind of teeth I will see many more of in the days to come--brown and rotted with smoke, the color of dead flowers, and covered by a slimy film.

I decide to move on, determined to find out how the process works, how one gets a doctor to write a note and then procures a coveted membership card from the club. I move to the back room. Everyone here is smoking, although smoking is forbidden on the first floor, and none of them has a membership card yet. I sit down next to Lily White and Billy Swain, two friends who met at the club three years ago. Lily says she has eye problems and sciatica, a pain in her leg and thigh. I ask how she got her doctor's note: "I asked my doctor to prescribe marijuana. He didn't want to do it. But all he needs to know is that I need it. I'm the patient. The doctors should know it's our life, it's in our hands, not the doctor's hands. Why, are you thinking about becoming a patient?"

I tell her I have no serious problems.

"The majority of people are facing something, anxiety or depression," she comforts. "You know what problems you got. Even if you just want to hang out. You got to approach it as honest as you can. Do you like what you see, or don't you?" Billy Swain agrees: "It's not so much that you have to get your doctor's permission. They have to say yes to you. The doctors should cater to you. You have to figure out if you're bored, if you need a social outlet. This is a happy place; there's a lot of hugging." A burly ponytailed man named Fred Martin joins the group. "Can I have a toke?" he asks Lily, and a toke is offered. A former Hell's Angel, Martin lost the bottom half of his right leg in a motorcycle accident. Now he works as a professional activist, usually across the street from the White House, where he yells at President Clinton as he jogs by, "Hey, I'll inhale for you." Fred offers his opinion on how I can join the club. "You women have a way of persuasion," he says, grinning, so I can admire his fine, mossy brown teeth. He picks up a pamphlet called Medical Marijuana: Know Your Rights put out by Peron, and reads it aloud: "`Talk with your doctor. Marijuana has been shown to: aid in stress management.' Don't you ever get stressed out?" he asks me. I look at him blankly, and he takes advantage of the silence to launch into the pot speech, something about Thomas Jefferson getting high, the Constitution on hemp paper, the War of 1812, Nancy Drew ....

At this point I had to stop. Total objectivity is a futile goal for all reporters, I realize. But there are times when personal circumstances so intrude on a reporter's judgment that they must be revealed. In this case, it could be that I have a boyfriend who drives me mad with his marijuana ravings, or that my uncle eased his cancer pains with marijuana, or that Dennis Peron is my best friend. As it happens, none of those things is true. What this reporter must admit is that at this point, I was very, very high. I had been sitting in this back room for quite some time and a cloud of smoke had risen level with my nose, giving me an acute case of contact high. I was not exactly hallucinating, but it seemed to me that everyone had stopped what they were doing and were staring at me. That Billy, Lily, Fred, even Van Gogh, were watching to see what I would do next. I decided it was time to go.

The next morning I returned to meet Dennis Peron. His office is behind a bolted door with no door knob, in a corner of the building. Inside is the combination of seedy and healthy living peculiar to California hippies--bits of weed and papers strewn about the stained carpet, alongside organic kemp meal and bottles of Arrowhead spring water. Dennis is like that, too, tanned but wrinkled, a wiry face and neatly combed white hair. I ask him why he started the club, and he begins, instantly, as if a switch had been thrown, to spin a heart-wrenching tale: "The club is a eulogy to my young lover Jonathan, who died of AIDS. We were lovers for seven years, and I miss him every day of my life. He died a very painful death. He had KS lesions all over his face, and we would go to a restaurant and people would move away from him. I always dreamed of a place Jonathan could go and smoke pot and meet people with AIDS and not feel such stigma. It started out as a eulogy and has turned into a mission of mercy for the most powerless and gentle members of society."

The story is completely rehearsed, emotionless. As he tells it, Peron flips through Post-it notes on his calendar, stops to shout to his coworkers to find out when his next radio interview is. It is only when I ask him who is responsible for Proposition 215 that I get his attention. "Me. You're looking at the guy. I am not an egomaniac, but it was my pain that changed the nation. My loss inspired me to do something for this country."

Like most tearjerker myths, Peron's leaves a few things out. Such as the fact that he was a notorious San Francisco drug dealer for decades before he started the club; he ran the Big Top supermarket, a one-stop drug emporium, and the Island Restaurant, which served pot upstairs and food downstairs, and was in and out of jail several times.

Later, when I tell Zimmerman about Peron's version of the story, he laughs for a good ten seconds before he explains Peron's role. "After two months it became clear that Dennis was going to fail miserably, that he wasn't keeping up with projections." They needed 800,000 signatures in five months to qualify the proposition, and Peron only had a few thousand. "By the time we were finished he had provided less than 10 percent of the signatures. There is no limit to that man's ego."

Peron does seem to be driven by an egotist's perverse, almost pathological need to shock. He believes he is infallible. He believes, actually, that he is literally a saint. He says things with no regard to the consequences, or perhaps too much regard. The most famous example is a quote he gave to The New York Times last year, a quote that was folded into the opponents' commercials, and cost Zimmerman countless hours of damage control: "I believe all marijuana use is medical--except for kids," he said. I ask Peron now if he regrets that quote. He stands up and glares at me. "no way do I regret it," he shouts. "I believe 90 percent to 100 percent of marijuana use is medical."

Needless to say, this attitude makes Peron's medical judgments less than scientific. He seems to judge medical need haphazardly; his only guiding principle is deference to the patient. For example, drug czar Barry McCaffrey, in his hostile December press conference, held up a chart he attributed to an ally of Peron's listing the medical uses of marijuana, including such dubious ailments as writer's cramp, aphrodisiac and recovering lost memories. "Aphrodisiac, that's ridiculous," Peron says, recalling the list. "They are just so uptight they had to throw in some sexual thing." What about the lost memories? "That's all right with me. Some people have demons, and they have to chase them away."

Narcotics agents busted him in August precisely for this laxness; among other things, they sent in an undercover female agent with a diagnosis of a yeast infection, and Peron sold her marijuana. He still does not understand why that's a problem. "I said to her, `I'm kind of embarrassed, this is a woman's thing, but maybe it helps the itching.' I'm not going to second guess a woman. I'd be putting down every woman in the world if I denied her medicine."

By the end of our talk, I have a better understanding of the process, although I'm not sure I have more faith in it. Peron is more careful than he used to be, more out of concern for narcs than for his patients. At his press conference, McCaffrey threatened to prosecute doctors who recommend the drug. This threat has ironically provided Peron with an easy excuse. "Everybody's being tricky," Peron says. "It's a semantic game forced on us by the federal government." The club operators ask only the minimum level of cooperation from the doctors: they check that the doctor is registered with the state licensing board, call the doctor, identify the club and check that the letter of diagnosis is real. Only if the doctor voices an objection will they deny the patient a membership card. It's an excuse, but not a great one. The other clubs still require a signed recommendation from the doctor. They also check with the doctor every six months or so to see that the diagnosis is still valid. Once a patient has a membership card from Peron's club, he has it forever.

The doctors who cooperate fall into three main categories. (1) Serious illness doctors. In cases of AIDS, cancer, glaucoma and epilepsy, there is substantial anecdotal evidence, although no thorough scientific research, that marijuana helps. For AIDS patients, it stimulates appetite; for cancer, it eases nausea associated with chemotherapy; for glaucoma, it relieves eye pressure; and, for epilepsy, it helps prevent seizures. (2) True believers. There are a handful of doctors who believe in marijuana's capacity to ease a myriad of symptoms. Most do independent research and monitor their patients carefully. (3) The skeptical but convinceable. Here is where the practice gets fishy.

Some doctors are wary of marijuana's effects, but willing to defer to their patient's wishes. Ironically, Proposition 215 permits them to cede control over marijuana much more than they could over, say, allergy medicine. An allergy medicine prescription has to be signed and numbered and tracked, with the number of refills designated. Marijuana merely has to be approved, and an oral approval will do. Dr. Barry Zevin runs the Tom Waddell Clinic in San Francisco, serving the poor and underserved. He says hundreds of his patients have asked him for letters of diagnosis to use at Peron's club. In 10 percent of the cases, mostly AIDS and cancer, he hands them over confidently. In 10 percent he advises against it, such as when the patient is severely psychotic. And for the rest he is not sure. But he will never deny a patient, even a psychotic one, a letter of diagnosis, and he is not sure he would ever make clear his objections. Because of his uncertainty, Peron's laxness suits him: "I try to educate my patients. I say, `The last thing in the world you need is marijuana. The last time you smoked it you became psychotic.' But if they still want a letter, it's a dilemma.... I prefer it to remain a gray area, where I don't need to make a decision." Even if Zevin persists in objecting, he may be won over. "Knowing them, they would have some advocacy," he says of the club operators. "They would call and say, `Would you reconsider? We have some research that shows marijuana helps hangnails, and I think this person ought to get it.' It's a process of negotiation."

But the real future of the wholesome marijuana movement is not in the hands of the sick; quite the opposite. People like Pebbles and Buzzy and, for that matter, Dennis Peron, are what they seem to be, relics of the past. I also met the future, and it was Starbucks. All over California, a new breed of young entrepreneur is busy these days opening up a new kind of head shop--excuse me, water pipe gallery--clean, safe, family-friendly places, with track lighting, juice bars and cafe lattes. In these places, what used to be known as a bong is now called art. And it costs as much.

In West Hollywood there is a street called Melrose that is determined not to ever, ever, not even on its worst hair day, look anything like the stretch of lower Market where Pebbles and Buzzy and Dennis get high. If Melrose met lower Market in an alley, it would call for a cop. On Melrose, trendy couture shops and MAC lipstick counters and retro diners ache for the B-list kitsch stores in their midst to disappear. So the merchants of Melrose must be thrilled by a store called Galaxy. With Galaxy, owner Russ Ceres has managed to turn something cheesy into class. Galaxy is the new wave of head shop, a place where smokers (ostensibly of tobacco) buy the finest of paraphernalia in the most dignified of settings. Gone are the Harley T-shirts, scorpion rings, fake silver chains; gone is the dimly lit bong room in back. In their place is a fluorescent-lit studio space, juice and coffee in front, water pipes displayed lovingly in glass cases, piece by precious piece, each accompanied by an embossed placard bearing the proud artist's name. Finally, bong pipes have reached equality with art, something deserving a room of its own (and a little wall space, and good lighting and maybe one day soon a show at the Whitney). "We are striving for a new level of intelligence," explains Ceres. "We want to take the Beavis and Butthead out of the image."

Ceres has a vision, and the core of his vision is bye-bye to Buzzy and Pebbles. With his sandy hair and J. Crew good looks, Ceres is a 27-year-old picture of healthy living, a younger, fitter version of Dennis Peron. "My worst nightmare is a seedy hippie place with tie-dyes that attracts the kind of crowd that crawls out of the woodwork," he explains. He pauses to frown, briefly but sharply, at his Thai iced coffee. Too much milk. "We are trying to upscale the atmosphere, to create more social acceptance for smoking. This is a positive place, where lawyers and doctors can go and wear nice clothes, like a cocktail lounge." He leads me over to the water pipe display, to show off some of his finest pieces--a rose and teal swirled eighteen-inch glass pipe, a twenty-one inch fashioned to look like the human anatomy. "People who know nothing about smoking are amazed at the artwork," he confides. "Sometimes they'll buy a piece just to display it on their coffee table."

The amazing thing about Ceres's vision is the total absence of rebellion. For those of you who suspected that the counterculture was really just a mass, commercialized culture masked, Ceres is the culmination of your theory. He does not reject middle-class norms, or even pretend to. In fact, he embraces all the modes of mainstream life--money, status, power. In his ideal America, marijuana would be anodyne, better than medicine. More like one of those cheerful balms that help take a rough corner or two off life--like a latte grande with skim, or a Disney theme park. It's not about revolution and sensual experiment. It's about family values. Drug laws bother him not because Big Brother is tying us down, but because "they break up families. They prevent children from communicating with their parents." In fact, his most cherished customer is "a 60-year-old man who came in and looked at me sternly and said, `Son, it's about time a place like this opened up. I'm tired of the tension this creates between families.'" Perhaps it's because the man reminds him of his own father, a white-collar vice president who, Ceres is pleased to report, "is very proud of me. He thinks it's great."

Part of Ceres's plan is to promote young entrepreneurs like him, people with a "sense of vision." One such person is the L.A. craftsman John Brown, the hands behind the Homemade brand of handcrafted water pipes. Brown works out of his parents' house in Brentwood, in a spotless room with hardwood floors, rattan furniture and a fish pond out front. On the day we meet the place hums with domestic tranquility, a lawn mower, a caged bird chirping somewhere. Brown is of the surfer school, buzzed yellow hair, slouchy jeans, says he's 21 but looks 16. He, too, began his business after a personal encounter with hippie sloth. "My old partner was a great kid but a real hippie. He followed the Dead shows and became real lazy and irresponsible, living on the road, spending all our capital. I have nothing against hippies, but I wouldn't want to work with one."

The experience seems to have left him with a bad taste for all things natural. Despite the company's crafty name, Brown prefers only synthetics. And he approaches his work with the enthusiasm Alexander Parkes must have felt when he discovered the myriad uses of plastic. "I consider myself a master of acrylics," he says, with deadpan pride. "I believe in the durability of acrylics. I use only the highest-quality acrylics, and I've experimented with the acrylics until it worked at perfection. I have made the perfect pipe." He demonstrates, by dropping the pipe on the floor, banging it on the table, showing how the stripes on the base look different if you view them at different angles.

Like Ceres, Brown believes he is onto something much larger than water pipes. "I got into it because of the age," he says, launching into MTV-speak. "I can feel the energy around me, how important it is. It's not a '60s thing anymore, it's not weed, it's not grass, it's the chronic. It's got a new name, a new lifestyle. It didn't go away. It just became modern."

Modern lifestyles require modern comforts and modern designs, and lucky for Brown and Ceres, they can find all they need, conveniently, in the new line of hemp products. While Brown was perfecting his acrylics, a parallel industry was sprouting nationwide to fill all his other worldly needs. Displayed in full glory in Hemp Times, the upscale improvement on High Times, the industry is dedicated to proving "an eco-friendly philosophy can equal big money." This month's issue, for example, features an inside look at the fashion show at Planet Hemp, New York's hemp megastore, where looks range from "Evening Elegance" to "Campus Classics." There is some attempt at a rebel yell--in one ad, a barefoot Keanu Reeves look-alike in an open hemp shirt squints dangerously from a busy street, as an army of blue suits passes him by. But mostly, the magazine is dedicated to proving you can tune in, turn on and cash in. "America's hemp products industry doubles its multimillion dollar grosses every year," the magazine's editors chirp.

There is hemp oil ("a `taste delicacy,' says Daniel Claret, one of North America's premier gourmet chefs"), hemp plaid ("and stripes too!"), hemp housewares and a hemp portfolio ("organize your life with hemp"). In the Hemper's Bazaar, you can find all the latest hemp fashions; women in bias-cut skirts cock their hips with Kate Moss haughtiness and tease each other's hair to prepare for a night out in their spaghetti-strap Corona hemp dresses. There are profiles of winning entrepreneurs, like Mitch and Jill Cahn. "Fed up with the whole Wall Street thing," Mitch explains, they turned to making hemp hats, and found they could "gross over two and a half million."

When all the buzz has faded, there is something a little bleak about the new pot atmosphere. Not that it might lead to legalization; that doesn't much bother me. But the air of sanctimony; the puffing up of marijuana into something more than it is. Jill and Mitch Cahn are annoying not because they are hucksters, but because they insist on believing that they are something more, that they're saving the earth by doling out hemp hats at Phish concerts. In the end, a head shop is just a head shop. The woman behind the counter at Galaxy looked as zoned out and faded as any bong salesgirl I've seen; and as Ceres was showing off his display of art pipes, one of his new intelligent clients was stealing my wallet.

For the sick, this blithe reverence for the herb seems especially grim. I suppose if you are a terminal AIDS or cancer patient, smoking pot every once in a while, even every day, can't hurt much. But knowing, even with medical certainty, that THC stimulates the anandamide neurotransmitter says nothing about what it does to your general well being. Pot may be medicine, but getting high every day is still getting high every day. And it can't be good for Dennis Peron's depressed stragglers and veterans on SSI to sit around getting high every day.

Spend a few days hanging around Peron's club, and you can get awfully sad at the pretense that all the wretched souls--the sick and the sick at heart--can be fixed by a hug and a toke. "There, there," said one of the nurses, stroking the arm of a woman who seemed hysterical and confused, maybe even mildly retarded. "I have a great idea. Let's go upstairs and have a smoke." It was a blind idolization I came to associate with something I saw in Peron's office: a framed photo of a robust, blooming pot plant propped up against an actual plant, withered and dying. My favorite patient at Cannabis Cultivators was Miguel Ciena, a 42-year-old with bone cancer, liver disease and AIDS. I liked Ciena because he was straight with me about what he was doing. He searched for no rationalizations, either for himself or the movement. He said he needed the medicine, but that he could do without it. He offered that he'd been smoking pot for twenty-eight years, long before he'd gotten sick. He didn't think it was too much to ask for patients to get a real recommendation from a willing doctor. And he thought the state was crazy to give Peron back his license after he'd failed them so badly the first time. I liked him most because he articulated what I had begun to feel: that human compassion was a complicated thing, different from giving a hungry kitten some milk. "They smile at you, but I wouldn't say they were caring," said Ciena. "Compassion is telling it like it is."

Anti-drug campaigners battling an epidemic of Ecstasy pill-taking among teenagers said he was being grossly irresponsible.

And at least one member of parliament called for the prosecution of Gallagher, whose recent hit single "Champagne Supernova" asks the musical question: "Where were you while we were getting high?"

But Gallagher, a guitarist in Britain's most successful pop group since the Beatles, was unrepentant. He said the outcry had prompted an honest debate about drugs.

Gallagher, whose brother Liam has been cautioned by police for possession of cocaine, said in a radio interview: "Drugs are like getting up and having a cup of tea in the morning.

"As soon as people realize that the majority of people in this country take drugs, then we'll be better off," he added.

Officials say 1 in 10 British teenagers may have experimented with Ecstasy, the synthetic drug of the rave culture. It first crossed the Atlantic from New York in the late 1980s.

Amphetamine-based and known as the "love drug," Ecstasy induces euphoria but can also cause hallucinations and a sense of panic.

Some British estimates put the number of weekly users as high as 500,000.

Gallagher, 29, also sprang to the defence of Brian Harvey, who was fired as lead singer of the group East 17 after saying taking Ecstasy was safe. The Oasis guitarist even claimed there were cocaine and heroin addicts in Britain's parliament.

The government swiftly condemned Gallagher. Home Office Minister Tom Sackville said: "For someone in his position to condone drug abuse is really stupid."

Fellow Conservative MP Tim Rathbone said authorities should "now investigate the bringing of criminal charges."

Controversial former judge James Pickles today backed Oasis star Noel Gallagher's call for the legalisation of drugs - saying the odds of being killed by Ecstasy were "one in a million."

The flamboyant Mr. Pickles said nicotine was a far bigger killer than other drugs in Britain and legalisation was "as inevitable as the end of Prohibition" in America.

Mr. Pickles, 71, was speaking in support of pop star Gallagher, who sparked a furious row earlier this week by saying that taking drugs was like having a cup of tea in the morning.

The former judge - who has long voiced his support for a more liberal approach to drugs - said Gallagher had ignited a "useful" debate.

Nicotine and alcohol caused hundreds of thousands of deaths each year, he said in an interview with Sky News.

He said: "Very few people die from these drugs.

"I know it hits the headlines, but it's one in a million - you've got as much chance of dying from Ecstasy as you have from being run over by a bus."

He said criminalisation was not working, was futile -- and wrong.

"You can get any drugs you want easily in this country today as long as you've got the money. We're fighting a hopeless war.

"It's time to stop prosecuting people and sending them to prison for abusing their own bodies. That's a matter for them. If they want to abuse their bodies, let them."

Mr. Pickles said the country should follow Holland's example, legalising soft drugs before slowly moving on to hard drugs, including heroin.

Insisting he had never taken drugs and did not condone their use, he said the law as it stood pushed the industry underground, raising prices and driving people into crime to pay for their habits.

He accused politicians - including Labour leader Tony Blair - of stifling debate on the issue.